IELTS Online

Đề thi IELTS Reading có đáp án mới nhất 2025-2026 [Cập nhật liên tục]

Mục lục [Ẩn]

- 1. Tổng hợp đề IELTS Reading có đáp án mới nhất

- 1.1. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 16.01.2026

- 1.2. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 04.01.2026

- 1.3. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 22.12.2025

- 1.4. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 24.11.2025

- 1.5. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 14.10.2025

- 2. Tổng hợp đề IELTS Reading có đáp án chi tiết

- 3. Chiến lược làm đề thi IELTS Reading hiệu quả

- 3.1. Chiến lược làm IELTS Reading Passage 1

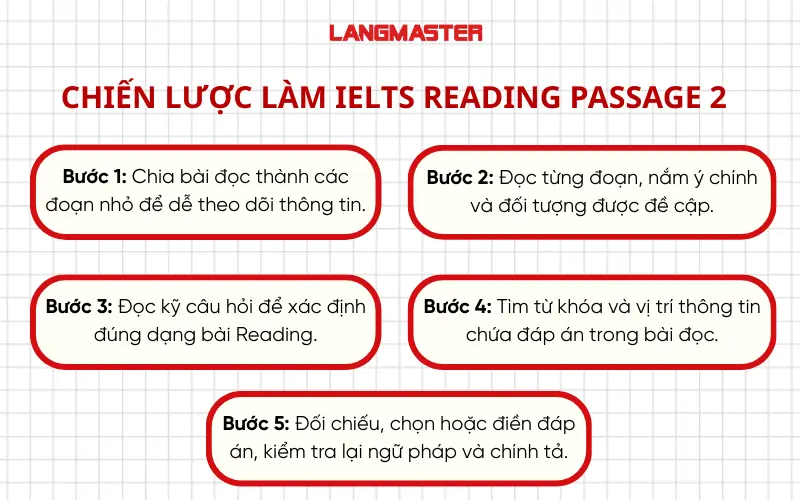

- 3.2. Chiến lược làm IELTS Reading Passage 2

- 3.3. Chiến lược làm IELTS Reading Passage 3

- 4. Nâng cao band điểm IELTS cùng khóa học IELTS online của Langmaster

IELTS Reading là một trong những kỹ năng “khó nhằn” nhất, đòi hỏi thí sinh không chỉ có vốn từ vựng học thuật tốt mà còn phải nắm vững chiến lược đọc hiểu, kỹ năng xác định thông tin và quản lý thời gian hiệu quả. Bài viết tổng hợp đề thi IELTS Reading có đáp án mới nhất 2025/2026, bao gồm đề thi thật và bộ IELTS Reading Cambridge chuẩn format. Tất cả đề đều đi kèm đáp án giúp bạn làm quen cấu trúc đề thi, rèn kỹ năng đọc hiểu học thuật và cải thiện tốc độ làm bài.

1. Tổng hợp đề IELTS Reading có đáp án mới nhất

1.1. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 16.01.2026

READING PASSAGE 1

Learning to Walk

These days the feet of a typical city dweller rarely encounter terrain any more uneven than a crack in the pavement. While that may not seem like a problem, it turns out that by flattening our urban environment we have put ourselves at risk of a surprising number of chronic illnesses and disabilities. Fortunately, the commercial market has come to the rescue with a choice of products. Research into the idea that flat floors could be detrimental to our health was pioneered back in the late 1960s in Long Beach, California. Podiatrist Charles Brantingham and physiologist Bruce Beekman were concerned with the growing epidemic of high blood pressure, varicose veins and deep-vein thromboses and reckoned they might be linked to the uniformity of the surfaces that we tend to stand and walk on.

The trouble, they believed, was that walking continuously on flat floors, sidewalks and streets concentrates forces on just a few areas of the foot. As a result, these surfaces are likely to be far more conducive to chronic stress syndromes than natural surfaces, where the foot meets the ground in a wide variety of orientations. They understood that the anatomy of the foot parallels that of the human hand – each having 26 bones, 33 joints and more than 100 muscles, tendons and ligaments – and that modern lifestyles waste all this potential flexibility.

Brantingham and Beekman became convinced that the damage could be rectified by making people wobble. To test their ideas, they got 65 factory workers to try standing on a variable terrain floor – spongy mats with varying degrees of resistance across the surface. This modest irregularity allowed the soles of the volunteers’ feet to deviate slightly from the horizontal each time they shifted position. As the researchers hoped, this simple intervention made a huge difference, within a few weeks. Even if people were wobbling slightly, it activated a host of muscles in their legs, which in turn helped pump blood back to their hearts. The muscle action prevented the pooling of blood in their feet and legs, reducing the stress on the heart and circulation. Yet decades later, the flooring of the world’s largest workplaces remains relentlessly smooth.

Earlier this year, however, the idea was revived when other researchers in the US announced findings from a similar experiment with people over 60. John Fisher and colleagues at the Oregon Research Institute in Eugene designed a mat intended to replicate the effect of walking on cobblestones*. In tests funded by the National Institute of Aging, they got some 50 adults to walk on the toots in their bare feet for less than an hour, three times a week. After 16 weeks, these people showed marked improvements in mobility, and even a significant reduction in blood pressure. People in a control group who walked on ordinary floors also improved but not as dramatically. The mats are now available for purchase and production is being scaled up. Even so, demand could exceed supply if this foot-stimulating activity really is a ‘useful non-pharmacological approach for preventing or controlling hypertension of older adults, as the researchers believe.

They are not alone in recognising the benefits of cobblestones. Reflexologists have long advocated walking on textured surfaces to stimulate so-called ‘acupoints’ on the soles of the feet. They believe that pressure applied to particular spots on the foot connects directly to particular organs of the body and somehow enhances their function. In China, spas, apartment blocks and even factories promote their cobblestone paths as healthful amenities. Fisher admits he got the concept from regular visits to the country. Here, city dwellers take daily walks along cobbled paths for five or ten minutes, perhaps several times a day, to improve their health. The idea is now taking off in Europe too.

People in Germany, Austria and Switzerland can now visit ‘barefoot parks’ and walk along ‘paths of the senses – with mud, logs, stone and moss underfoot. And it is not difficult to construct your own path with simple everyday objects such as stones or bamboo poles. But if none of these solutions appeal, there is another option. A new shoe on the market claims to transform flat, hard, artificial surfaces into something like uneven ground. ‘These shoes have an unbelievable effect,’ says Benno Nigg, an exercise scientist at Calgary University in Canada.

Known as the Masai Barefoot Technology, the shoes have rounded soles that cause you to rock slightly when you stand still, exercising the small muscles around the ankle that are responsible for stability. Forces in the joint are reduced, putting less strain on the system, Nigg claims.

Some of these options may not appeal to all consumers and there is a far simpler alternative. If the urban environment is detrimental to our health, then it is obvious where we should turn. A weekend or even a few hours spent in the countryside could help alleviate a sufferer’s aches and pains, and would require only the spending of time.

However, for many modern citizens, the countryside is not as accessible as it once was and is in fact a dwindling resource. Our concrete cities are growing at a terrifying rate – perhaps at the same rate as our health problems.

Questions 1 – 5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage? Write:

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

1. Brantingham and Beekman were the first researchers to investigate the relationship between health problems and flat floors.

2. The subjects in Fisher’s control group experienced a decline in their physical condition.

3. The manufacturers are increasing the number of cobblestone mats they are making.

4. Fisher based his ideas on what he saw during an overseas trip.

5. The Masai Barefoot Technology shoes are made to fit people of all ages.

Questions 6 – 8

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 6 – 8 on your answer sheet.

6. The writer suggests that Brantingham and Beekman’s findings were

A. ignored by big companies.

B. doubted by other researchers.

C. applicable to a narrow range of people.

D. surprising to them.

7. What claim is made by the designers of the cobblestone mats?

A. They need to be used continuously in order to have a lasting effect.

B. They would be as beneficial to younger people as to older people.

C. They could be an effective alternative to medical intervention.

D. Their effects may vary depending on individual users.

8. Which of the following points does the writer make in the final paragraph?

A. People should question new theories that scientists put forward.

B. High prices do not necessarily equate to a quality product.

C. People are setting up home in the country for health reasons.

D. The natural environment is fast disappearing.

Questions 9 – 14

Complete the summary below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 9-14 on your answer sheet.

In their research, Brantingham and Beekman looked at the complex physical 9.______ of the foot and noted that the surfaces of modem environments restrict its movement. They invented a mat which they tried out on factory workers. Whenever the workers walked on it, the different levels of 10.______ in the mat would encourage greater muscle action. In turn, this lessened the effect of 11.______ on the cardiovascular system. Similar research was undertaken by John Fisher and colleagues in Oregon. As a result of their findings, they decided to market cobblestone mats to the elderly as a means of dealing with 12.______ . Reflexologists claim that by manipulating specific parts of the feet, the performance of certain 13.______ will also improve. Finally, Benno Nigg at Calgary University believes that specially shaped 14.______ on shoes should give health benefits.

Đáp án

|

1. TRUE |

8. D |

|

2. FALSE |

9. anatomy |

|

3. TRUE |

10. resistance |

|

4. TRUE |

11. stress |

|

5. NOT GIVEN |

12. hypertension |

|

6. A |

13. organs |

|

7. C |

14. soles |

READING PASSAGE 2

Yawning

How and why we yarn still presents problems for researchers in an area which has only recently been opened up to study

When Robert R Provine began studying yawning in the 1960s, it was difficult for him to convince research students of the merits of ‘yawning science1. Although it may appear quirky to some, Provine’s decision to study yawning was a logical extension of his research in developmental neuroscience.

The verb ‘to yawn’ is derived from the Old English ganien or ginian, meaning to gape or open wide. But in addition to gaping jaws, yawning has significant features that are easy to observe and analyse. Provine ‘collected’ yawns to study by using a variation of the contagion response*. He asked people to ‘think about yawning’ and, once they began to yawn to depress a button and that would record from the start of the yawn to the exhalation at its end.

Provine’s early discoveries can be summanized as follows: the yawn is highly stereotyped but not invariant in its duration and form. It is an excellent example of the instinctive ‘fixed action pattern’ of classical animal-behavior study, or ethology. It is not a reflex (short-duration, rapid, proportional response to a simple stimulus), but, once started, a yawn progresses with the inevitability of a sneeze. The standard yawn runs its course over about six seconds on average, but its duration can range from about three seconds to much longer than the average. There are no half-yawns: this is an example of the typical intensity of fixed action patterns and a reason why you cannot stifle yawns. Just like a cough, yawns can come in bouts with a highly variable inter-yawn interval, which is generally about 68 seconds but rarely more than 70. There is no relation between yawn frequency and duration: producers of short or long yawns do not compensate by yawning more or less often. Furthermore, Provine’s hypotheses about the form and function of yawning can be tested by three informative yawn variants which can be used to look at the roles of the nose, the mouth and the jaws.

i) The closed nose yawn

Subjects are asked to pinch their nose closed when they feel themselves start to yawn. Most subjects report being able to perform perfectly normal closed nose yawns. This indicates that the inhalation at the onset of a yawn, and the exhalation at its end, need not involve the nostrils – the mouth provides a sufficient airway.

ii) The clenched teeth yawn

Subjects are asked to clench their teeth when they feel themselves start to yawn but allow themselves to inhale normally through their open lips and clenched teeth. This variant gives one the sensation of being stuck midyawn. This shows that gaping of the jaws is an essential component of the fixed action pattern of the yawn, and unless it is accomplished, the program (or pattern) will not run to completion. The yawn is also shown to be more than a deep breath, because, unlike normal breathing, inhalation and exhalation cannot be performed so well through the clenched teeth as through the nose.

iii) The nose yawn

This variant tests the adequacy of the nasal airway to sustain a yawn. Unlike normal breathing, which can be performed equally well through mouth or nose, yawning is impossible via nasal inhalation alone. As with the clenched teeth yawn, the nose yawn provides the unfulfilling sensation of being stuck in mid-yawn. Exhalation, on the other hand, can be accomplished equally well through nose or mouth. Through thin methodology Provine demonstrated that inhalation through the oral airway and the gaping of jaws are necessary for normal yawns. The motor program for yawning will not run to completion without feedback that these parts of the program have been accomplished.

But yawning is a powerful, generalized movement that involves much more than airway maneuvres and jaw-gaping. When yawning you also stretch your facial muscles, tilt your head back, narrow or close your eyes, produce tears, salivate, open the Eustachian tubes of your middle ear and perform many other, yet unspecified, cardiovascular and respiratory acts. Perhaps the yawn shares components with other behaviour. For example, in the yawn a kind of ‘slow sneeze1 or is the sneeze a ‘fast yawn’? Both share common respiratory and other features including jaw gaping, eye closing and head tilting.

Yawning and stretching share properties and may be performed together as parts of a global motor complex. Studies by J I p deVries et al. in the early 1980s, charting movement in the developing foet US using ultrasound, observed a link between yawning and stretching. The most extraordinary demonstration of the yawn-stretch linkage occurs in many people paralyzed on one side of their body because of brain damage caused by a stroke, the prominent British neurologist Sir Francis Walshe noted in 1923 that when these people yawn, they are startled and mystified to observe that their otherwise paralyzed arm rises and flexes automatically in what neurologists term an ‘associated response’. Yawning apparently activates undamaged, unconsciously controlled connections between the brain and the motor system, causing the paralyzed limb to move. It is not known whether the associated response is a positive prognosis for recovery, nor whether yawning is therapeutic for prevention of muscular deterioration.

Provine speculated that, in general, yawning may have many functions, and selecting a single function from the available options may be an unrealistic goal. Yawning appears to be associated with a change of behavioral state, switching from one activity to another. Yawning is also a reminder that ancient and unconscious behavior linking US to the animal world lurks beneath the veneer of culture, rationality and language.

(Nguồn Internet)

Questions 15 – 20

Complete the summary below using the list of words, A-K, below

Write the correct letter, A-K, in boxes 15-20 on your answer sheet.

Provine’s early findings on yawns

Through his observation of yawns, Province was able to confirm that 1.______ do not exist.

Just like a 2._______, yawns cannot be interrupted after they have begun. This is because yawns occur as a 3.______ rather than a stimulus response as was previously thought.

In measuring the time taken to yawn, provive found that a typical yawn lasts about 4.______. He also found that it is a common for people to yawn a number of times in quick succession with the yawns usually being around 5._____ apart. When studying whether length and rate were connected. Province concluded that people who yawn less do not necessarily produce 6._____ to make up for this.

A. form and function

B. long yawns

C. 3 seconds

D. fixed action pattern

E. 68 seconds

F. short yawns

G. reflex

H. sneeze

I. short duration

J. 6 seconds

K. half-yawns

Questions 20 – 24

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 20 – 24 on your answer sheet.

20. What did Provine conclude from his ‘closed nose yawn1 experiment?

A Ending a yawn requires use of the nostrils.

B You can yawn without breathing through your nose

C Breathing through the nose produces a silent yawn.

D The role of the nose in yawning needs further investigation.

21. Provine’s clenched teeth yawn’s experiment shows that

A yawning is unconnected with fatigue.

B a yawn is the equivalent of a deep intake of breath.

C you have to be able to open your mouth wide to yawn.

D breathing with the teeth together is as efficient as through the nose.

22. The nose yawn experiment was used to test weather yawning

A can be stopped after it has stated

B is the result of motor programing

C involves both inhalation and exhalation.

D can be accomplished only through the nose.

23. In people paralyzed on one side because of brain damage

A yawning may involve only one side of the face.

B the yawing response indicates that recovery is likely

C movement in paralysed arm is stimulated by yawming

D yawning can be used as an example to prevent muscle wasting.

24. In the last paragraph, the writer concludes that

A yawning is a sign of boredom.

B we yawn is spite of the development of our species

C yawning is a more passive activity than we Imagine

D we are stimulated to yawn when our brain activity is low.

Questions 25 – 27

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage?

In boxes 25-27 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

25. Research students were initially reluctant to appreciate the value of Provine’s studies.

26. When foetuses yawn and stretch they are learning how to control movement.

27. According to Provine, referring to only one function is probably inadequate to explain why people yawn.

Đáp án

|

15. K |

21. C |

|

16. H |

22. B |

|

17. D |

23. C |

|

18. J |

24. B |

|

19. E |

25. YES |

|

20. B |

26. NOT GIVEN |

|

21. B |

27. YES |

>>> XEM THÊM: Giải đề IELTS Reading: The Evolutionary Mystery: Crocodile Survives

READING PASSAGE 3

Endangered languages

‘Nevermind whales, save the languages’, says Peter Monaghan, graduate of the Australian National University

Worried about the loss of rain forests and the ozone layer? Well, neither of those is doing any worse than a large majority of the 6,000 to 7,000 languages that remain in use on Earth. One half of the survivors will growing evidence that not all approaches to the almost certainly be gone by 2050, while 40% more preservation of languages will be particularly will probably be well on their way out. In their place, almost all humans will speak one of a handful of megalanguages – Mandarin, English, Spanish.

Linguists know what causes languages to disappear, but less often remarked is what happens on the way to disappearance: languages’ vocabularies, grammars and expressive potential all diminish as one language is replaced by another. ‘Say a community goes over from speaking a traditional Aboriginal language to speaking a creole*,’ says Australian Nick Evans, a leading authority on Aboriginal languages, ‘you leave behind a language where there’s very fine vocabulary for the landscape. All that is gone in a creole. You’ve just got a few words like ‘gum tree’ or whatever. As speakers become less able to express the wealth of knowledge that has filled ancestors’ lives with meaning over millennia, it’s no wonder that communities tend to become demoralised.’

If the losses are so huge, why are relatively few linguists combating the situation? Australian linguists, at least, have achieved a great deal in terms of preserving traditional languages. Australian governments began in the 1970s to support an initiative that has resulted in good documentation of most of the 130 remaining Aboriginal languages. In England, another Australian, Peter Austin, has directed one of the world’s most active efforts to limit language loss, at the University of London. Austin heads a programme that has trained many documentary linguists in England as well as in language-loss hotspots such as West Africa and South America.

At linguistics meetings in the US, where the endangered-language issue has of late been something of a flavour of the month, there is growing evidence that not all approaches to the preservation of languages will be particularly helpful. Some linguists are boasting, for example, of more and more sophisticated means of capturing languages: digital recording and storage, and internet and mobile phone technologies. But these are encouraging the ‘quick dash’ style of recording trip: fly in, switch on digital recorder, fly home, download to hard drive, and store gathered material for future research. That’s not quite what some endangered-language specialists have been seeking for more than 30 years. Most loud and untiring has been Michael Krauss, of the University of Alaska. He has often complained that linguists are playing with non-essentials while most of their raw data is disappearing.

Who is to blame? That prominent linguist Noam Chomsky, say Krauss and many others. Or, more precisely, they blame those linguists who have been obsessed with his approaches. Linguists who go out into communities to study, document and describe languages, argue that theoretical linguists, who draw conclusions about how languages work, have had so much influence that linguistics has largely ignored the continuing disappearance of languages. Chomsky, from his post at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has been the great man of theoretical linguistics for far longer than he has been known as a political commentator. His landmark work of 1957 argues that all languages exhibit certain universal grammatical features, encoded in the human mind. American linguists, in particular, have focused largely on theoretical concerns ever since, even while doubts have mounted about Chomsky’s universals.

Austin and Co. are in no doubt that because languages are unique, even if they do tend to have common underlying features, creating dictionaries and grammars requires prolonged and dedicated work. This requires that documentary linguists observe not only languages’ structural subtleties, but also related social, historical and political factors. Such work calls for persistent funding of field scientists who may sometimes have to venture into harsh and even hazardous places. Once there, they may face difficulties such as community suspicion. As Nick Evans says, a community who speak an endangered language may have reasons to doubt or even oppose efforts to preserve it. They may have seen support and funding for such work come and go. They may have given up using the language with their children, believing they will benefit from speaking a more widely understood one.

Plenty of students continue to be drawn to the intellectual thrill of linguistics field work. That’s all the more reason to clear away barriers, contend Evans, Austin and others. The highest barrier, they agree, is that the linguistics profession’s emphasis on theory gradually wears down the enthusiasm of linguists who work in communities. Chomsky disagrees. He has recently begun to speak in support of language preservation. But his linguistic, as opposed to humanitarian, argument is, let’s say, unsentimental: the loss of a language, he states, ‘is much more of a tragedy for linguists whose interests are mostly theoretical, like me, than for linguists who focus on describing specific languages, since it means the permanent loss of the most relevant data for general theoretical work’. At the moment, few institutions award doctorates for such work, and that’s the way it should be, he reasons. In linguistics, as in every other discipline, he believes that good descriptive work requires thorough theoretical understanding and should also contribute to building new theory. But that’s precisely what documentation does, objects Evans. The process of immersion in a language, to extract, analyse and sum it up, deserves a PhD because it is ‘the most demanding intellectual task a linguist can engage in’.

(Nguồn Internet)

Questions 27-32

Do the following statements agree with the views of the author in the Reading Passage? Write in boxes 27-32 on your answer sheet

YES if the statement matches the information

NO if the statement does not match with the information

NOT GIVEN if no information is available

27. By 2050 only a small number of languages will be flourishing.

28. Australian academics’ efforts to record existing Aboriginal languages have been too limited.

29. The use of technology In language research is proving unsatisfactory in some respects.

30. Chomsky’s political views have overshadowed his academic work.

31. Documentary linguistics studies require long-term financial support.

32. Chomsky’s attitude to disappearing languages is too emotional.

Question 33-36

Choose appropriate options A, B, C or D.

33. The writer mentions rainforests and the ozone layer.

A. because he believes anxiety about environmental issues is unfounded.

B. to demonstrate that academics in different disciplines share the same problems.

C. because they exemplify what is wrong with the attitudes of some academics.

D. to make the point that the public should be equally concerned about languages.

34. What does Nick Evans say about speakers of a creole?

A. They lose the ability to express ideas which are part of their culture.

B. Older and younger members of the community have difficulty communicating.

C. They express their ideas more clearly and concisely than most people.

D. Accessing practical information causes problems for them.

35. What is similar about West Africa and South America, from the linguist’s point of view?

A. The English language is widely used by academics and teachers.

B. The documentary linguists who work there were trained by Australians.

C. Local languages are disappearing rapidly in both places.

D. There are now only a few undocumented languages there.

36. Michael Krauss has frequently pointed out that

A. linguists are failing to record languages before they die out.

B. linguists have made poor use of improvements in technology.

C. linguistics has declined in popularity as an academic subject.

D. linguistics departments are underfunded in most universities.

Question 37-40

Complete each sentence with the correct ending A-G below.

Write the correct letter A-G.

List of Endings

A. even though it is in danger of disappearing.

B. provided that it has a strong basis in theory.

C. although it may share certain universal characteristics

D. because there is a practical advantage to it

E. so long as the drawbacks are clearly understood.

F. in spite of the prevalence of theoretical linguistics.

G. until they realize what is involved

37. Linguists like Peter Austin believe that every language is unique

38. Nick Evans suggests a community may resist attempts to save its language

39. Many young researchers are interested in doing practical research

40. Chomsky supports work in descriptive linguistics

Đáp án

|

27. YES |

34. A |

|

28. NO |

35. C |

|

29. YES |

36. A |

|

30. NOT GIVEN |

37. C |

|

31. YES |

38. A |

|

32. NO |

39. F |

|

33. D |

40. B |

>>> XEM THÊM: Giải đề Cam 17, Test 4 Reading passage 3 - Timur Gareyev

1.2. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 04.01.2026

READING PASSAGE 1

The Ant and the Mandarin

In 1476, the farmers of Berne in Switzerland decided there was only one way to rid their fields of the cutworms attacking their crops. They took the pests to court. The worms were tried, found guilty and excommunicated by the archbishop. In China, farmers had a more practical approach to pest control. Rather than relying on divine intervention, they put their faith in frogs, ducks and ants. Frogs and ducks were encouraged to snap up the pests in the paddies and the occasional plague of locusts. But the notion of biological control began with an ant. More specifically, it started with the predatory yellow citrus ant Oeco-phylla smaragdina, which has been polishing off pests in the orange groves of southern China for at least 1,700 years. The yellow citrus ant is a type of weaver ant, which binds leaves and twigs with silk to form a neat, tent-like nest. In the beginning, farmers made do with the odd ants’ nests here and there. But it wasn’t long before growing demand led to the development of a thriving trade in nests and a new type of agriculture – ant farming.

For an insect that bites, the yellow citrus ant is remarkably popular. Even by ant standards, Oecophylla smaragdina is a fearsome predator. It’s big, runs fast and has a powerful nip – painful to humans but lethal to many of the insects that plague the orange groves of Guangdong and Guangxi in southern China. And for at least 17 centuries, Chinese orange growers have harnessed these six-legged killing machines to keep their fruit groves healthy and productive.

Citrus fruits evolved in the Far East and the Chinese discovered the delights of their flesh early on. As the ancestral home of oranges, lemons and pomelos, China also has the greatest diversity of citrus pests. And the trees that produce the sweetest fruits, the mandarins – or kan – attract a host of plant-eating insects, from black ants and sap-sucking mealy bugs to leaf-devouring caterpillars. With so many enemies, fruit growers clearly had to have some way of protecting their orchards.

The West did not discover the Chinese orange growers’ secret weapon until 1 the early 20th century. At the time, Florida was suffering an epidemic of citrus canker and in 1915 Walter Swingle, a plant physiologist working for the US Department of Agriculture, was sent to China in search of varieties of orange that were resistant to the disease. Swingle spent some time studying the citrus orchards around Guangzhou, and there he came across the story of the cultivated ant. These ants, he was told, were “grown” by the people of a small village nearby who sold them to the orange growers by the nestful.

The earliest report of citrus ants at work among the orange trees appeared in a book on tropical and subtropical botany written by Hsi Han in AD 304. “The people of Chiao-Chih sell in their markets ants in bags of rush matting. The nests are like silk. The bags are all attached to twigs and leaves which, with the i ants inside the nests, are for sale. The ants are reddish-yellow in colour, bigger than ordinary ants. In the south, if the kan trees do not have this kind of ant, the fruits will all be damaged by many harmful insects, and not a single fruit will be perfect.”

Initially, farmers relied on nests which they collected from the wild or bought in the market where trade in nests was brisk. “It is said that in the south orange trees which are free of ants will have wormy fruits. Therefore, people race to buy nests for their orange trees,” wrote Liu Hsun in Strange Things Noted in the South in about 890.

The business guickly became more sophisticated. From the 10th century, country people began to trap ants in artificial nests baited with fat. “Fruit-growing families buy these ants from vendors who make a business of collecting and selling such creatures,” wrote Chuang Chi-Yu in 1130. “They trap them by filling hogs’ or sheep’s bladders with fat and placing them with the cavities open next to the ants’ nests. They wait until the ants have migrated into the bladders and take them away. This is known as ‘rearing orange ants’.” Farmers attached k the bladders to their trees, and in time the ants spread to other trees and built new nests.

By the 17th century, growers were building bamboo walkways between their trees to speed the colonisation of their orchards. The ants ran along these narrow bridges from one tree to another and established nests “by the hundreds of thousands”.

Did it work? The orange growers clearly thought so. One authority, Chhii Ta-Chun, writing in 1700, stressed how important it was to keep the fruit trees free of insect pests, especially caterpillars. “It is essential to eliminate them so that the trees are not injured. But hand labour is not nearly as efficient as ant power…”

Swingle was just as impressed. Yet despite his reports, many Western biologists were sceptical. In the West, the idea of using one insect to destroy another was new and highly controversial. The first breakthrough had come in 1888, when the infant orange industry in California had been saved from extinction by the Australian vedalia beetle. This beetle was the only thing that had made any in- T roads into the explosion of cottony cushion scale that was threatening to destroy the state’s citrus crops. But, as Swingle now knew, California’s “first” was nothing of the sort. The Chinese had been expert in biocontrol for many centuries.

The long tradition of ants in the Chinese orchards only began to waver in the 1950s and 1960s with the introduction of powerful organic insecticides. Although most fruit growers switched to chemicals, a few hung onto their ants. Those who abandoned ants in favour of chemicals quickly became disillusioned. As costs soared and pests began to develop resistance to the chemicals, growers began to revive the old ant patrols in the late 1960s. They had good reason to have faith in their insect workforce.

Research in the early 1960s showed that as long as there were enough ants in the trees, they did an excellent job of dispatching some pests – mainly the larger insects – and had modest success against others. Trees with yellow ants produced almost 20 per cent more healthy leaves than those without. More recent trials have shown that these trees yield just as big a crop as those protected by expensive chemical sprays.

One apparent drawback of using ants – and one of the main reasons for the early scepticism by Western scientists – was that citrus ants do nothing to control mealy bugs, waxy-coated scale insects which can do considerable damage to fruit trees. In fact, the ants protect mealy bugs in exchange for the sweet honey-dew they secrete. The orange growers always denied this was a problem but Western scientists thought they knew better.

Research in the 1980s suggests that the growers were right all along. Where X mealy bugs proliferate under the ants’ protection, they are usually heavily parasitised and this limits the harm they can do.

Orange growers who rely on carnivorous ants rather than poisonous chemicals maintain a better balance of species in their orchards. While the ants deal with the bigger insect pests, other predatory species keep down the numbers of smaller pests such as scale insects and aphids. In the long run, ants do a lot less damage than chemicals – and they’re certainly more effective than excommunication.

Questions 1-5

Look at the following events (Questions 1-5) and the list of dates below.

Match each event with the correct time A-G.

Write the correct letter A-G in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

1 The first description of citrus ants is traded in the marketplace.

2 Swingle came to Asia for research.

3 The first record of one insect is used to tackle other insects in the western world.

4 Chinese fruit growers started to use pesticides in place of citrus ants.

5 Some Chinese farmers returned to the traditional bio-method.

List of Dates

A 1888

B AD 890

C AD 304

D 1950s

E 1960s

F 1915

G 1130

Questions 6-13

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage?

In boxes 6-13 on your answer sheet write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

6 China has more citrus pests than any other country in the world.

7 Swingle came to China to search for an insect to bring back to the US.

8 Many people were very impressed by Swingle’s discovery.

9 Chinese farmers found that pesticides became increasingly expensive.

10 Some Chinese farmers abandoned the use of pesticide.

11 Trees with ants had more leaves fall than those without.

12 Fields using ants yield as large a crop as fields using chemical pesticides.

13 Citrus ants often cause considerable damage to the bio-environment of the orchards.

Đáp án

|

1. C |

8. FALSE |

|

2. F |

9. TRUE |

|

3. A |

10. TRUE |

|

4. D |

11. FALSE |

|

5. E |

12. TRUE |

|

6. TRUE |

13. FALSE |

|

7. FALSE |

READING PASSAGE 2

Multitasks

A. Do you read while listening to music? Do you like to watch TV while finishing your homework? People who have these kinds of habits are called multi-taskers. Multitasks are able to complete two tasks at the same time by dividing their focus. However, Thomas Lehman, a researcher in Psychology, believes people never really do multiple things simultaneously. Maybe a person is reading while listening to music, but in reality, the brain can only focus on one task. Reading the words in a book will cause you to ignore some of the words of the music. When people think they are accomplishing two different tasks efficiently, what they are really doing is dividing their focus. While listening to music, people become less able to focus on their surroundings. For example, we all have experience of times when we talk with friends and they are not responding properly. Maybe they are listening to someone else talk, or maybe they are reading a text on their smart phone and don’t hear what you are saying. Lehman called this phenomenon “email voice”.

B. The world has been changed by computers and its spin offs like smart-phones or cellphones. Now that most individuals have a personal device, like a smart-phone or a laptop, they are frequently reading, watching or listening to virtual information. This raises the occurrence of multitasking in our day to day life. Now when you work, you work with your typewriter, your cellphone, and some colleagues who may drop by at any time to speak with you. In professional meetings, when one normally focuses and listens to one another, people are more likely to have a cell phone in their lap, reading or communicating silently with more people than ever, even inventions such as the cordless phone have increased multitasking. In the old days, a traditional wall phone would ring, and then the housewife would have to stop her activities to answer it. When it rang, the housewife will sit down with her legs up, and chat, with no laundry or sweeping or answering the door. In the modern era, our technology is convenient enough to not interrupt our daily tasks.

C. Earl Miller, an expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, studied the prefrontal cortex, which controls the brain while a person is multitasking. According to his studies, the size of this cortex varies between species, He found that for humans, the size of this part constitutes one third of the brain, while it is only 4 to 5 percent in dogs, and about 15% in monkeys. Given that this cortex is larger on a human, it allows a human to be more flexible and accurate in his or her multitasking. However, Miller wanted to look further into whether the cortex was truly processing information about two different tasks simultaneously. He designed an experiment where he presents visual stimulants to his subjects in a wax that mimics multi-tasking. Miller then attached sensors to the patients’ heads to pick up the electric patterns of the brain. This sensor would show if the brain particles, called neurons, were truly processing two different tasks. What he found is that the brain neurons only lit up in singular areas one at a time, and never simultaneously.

D. Davis Meyer, a professor of University of Michigan, studied the young adults in a similar experiment. He instructed them to simultaneously do math problems and classify simple words into different categories. For this experiment, Meyer found that when you think you are doing several jobs at the same time, you are actually switching between jobs. Even though the people tried to do the tasks at the same time, and both tasks were eventually accomplished, overall, the task took more time than if the person focused on a single task one at a time.

E. People sacrifice efficiency when multitasking, Gloria Mark set office workers as his subjects. He found that they were constantly multitasking. He observed that nearly every 11 minutes people at work were disrupted. He found that doing different jobs at the same time may actually save time. However, despite the fact that they are faster, it does not mean they are more efficient. And we are equally likely to self-interrupt as be interrupted by outside sources. He found that in office nearly every 12 minutes an employee would stop and with no reason at all, check a website on their computer, call someone or write an email. If they concentrated for more than 20 minutes, they would feel distressed. He suggested that the average person may suffer from a short concentration span. This short attention span might be natural, but others suggest that new technology may be the problem. With cellphones and computers at our sides at all times, people will never run out of distractions. The format of media, such as advertisements, music, news articles and TV shows are also shortening, so people are used to paying attention to information for a very short time.

F. So even though focusing on one single task is the most efficient way for our brains to work, it is not practical to use this method in real life. According to human nature, people feel more comfortable and efficient in environments with a variety of tasks, Edward Hallowell said that people are losing a lot of efficiency in the workplace due to multitasking, outside distractions and self-distractions. As it matters of fact, the changes made to the workplace do not have to be dramatic. No one is suggesting we ban e-mail or make employees focus on only one task. However, certain common workplace tasks, such as group meetings, would be more efficient if we banned cell-phones, a common distraction. A person can also apply these tips to prevent self-distraction. Instead of arriving to your office and checking all of your e-mails for new tasks, a common workplace ritual, a person could dedicate an hour to a single task first thing in the morning. Self-timing is a great way to reduce distraction and efficiently finish tasks one by one, instead of slowing ourselves down with multi-tasking.

(Nguồn: Internet)

Questions 14-18

Reading Passage 2 has six paragraphs, A-F.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

14. A reference to a domestic situation that does not require multitasking

15. A possible explanation of why we always do multitask together

16. A practical solution to multitask in work environment

17. Relating multitasking to the size of prefrontal cortex

18. Longer time spent doing two tasks at the same time than one at a time

Questions 19-23

Look at the following statements (Questions 6-10) and the list of scientists below.

Match each statement with the correct scientist, A-E.

Write the correct letter, A-E, in boxes 6-10 on your answer sheet. NB You may use any letter more than once.

A. Thomas Lehman

B. Earl Miller

C. David Meyer

D. Gloria Mark

E. Edward Hallowell

19. When faced multiple visual stimulants, one can only concentrate on one of them.

20. Doing two things together may be faster but not better.

21. People never really do two things together even if you think you do.

22. The causes of multitask lie in the environment.

23. Even minor changes in the workplace will improve work efficiency.

Questions 24-26

Complete the sentences below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 24-26 on your answer sheet.

A term used to refer to a situation when you are reading a text and cannot focus on your surroundings is 24.______.

The 25.______ part of the brain controls multitasking.

The practical solution of multitask in work is not to allow use of cellphone in 26._____.

|

14. B |

21. A |

|

15. F |

22. D |

|

16. F |

23. E |

|

17. C |

24. email voice |

|

18. D |

25. prefrontal cortex |

|

19. B |

26. group meetings |

|

20. D |

READING PASSAGE 3

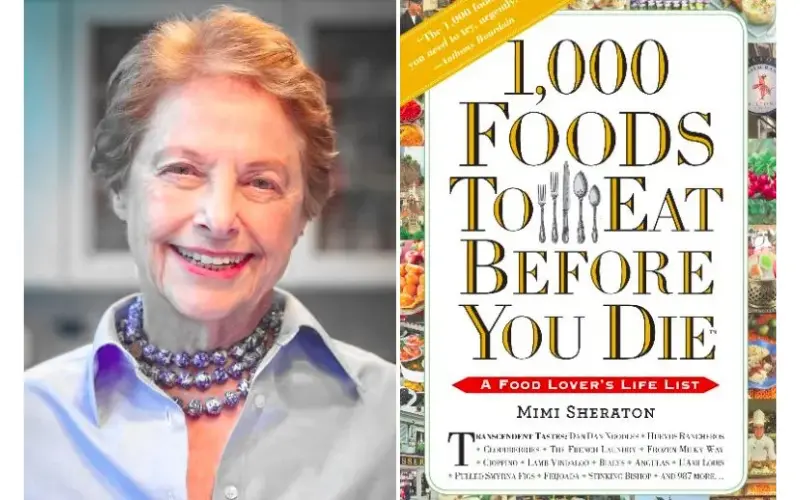

hat Are the 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die?

Written by a former New York Times restaurant critic, this tome will keep your appetite satisfied for a lifetime.

When was the last time you sat down to a meal of harnam meshwi, a.k.a. grilled pigeon, which is most likely found on a menu in Egypt? Or traveled to Oslo, Norway, for a breakfast of freshly caught shrimp? Chances are probably never. However, thanks to former New York Times restaurant critic, Smithsonian contribution and author Mimi Sheraton’s latest book, 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die, your foodie life is about to get a whole lot more interesting.

Inspired by Patricia Schultz’s best-selling 1,000 Places to See Before You Die (also published by Workman Publishing), Sheraton has rounded up 1,000 must-try dishes, restaurants, markets, cultural feasts, and even some relatively universal foods (such as bananas, olive oil, and whipped cream) that transcend regional categorization. Curated from cuisines around the globe, Sheraton has put them together in one large volume, along with details on historic and cultural context, tips on how to prepare or where to try a particular dish, and even several dozen recipes. It’s a project that’s been 10 years in the making—one that’s as much a wonderful display of Sheraton’s vast food knowledge (she’s been writing about food for 60 years) as it is an ode to the world’s sheer culinary diversity.

The ultimate gift for the food lover. In the same way that 1,000 Places to See Before You Die reinvented the travel book, 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die is a joyous, informative, dazzling, mouthwatering life list of the world’s best food. The book is organized not by country or type of food, but rather by the experience of eating itself. Sections guide the reader through “Street Food & Snacks,” “Comfort Food,” and “Sweets & Treats,” among others. This structure encourages serendipitous discovery, where a reader looking for a classic French pastry might stumble upon a traditional Indonesian dessert and become captivated. Sheraton’s entries are more than just lists; they are miniature stories. She explains why a specific cheese from a remote village in Greece is worth seeking out, or how a particular noodle dish embodies the history of trade routes in Southeast Asia. This narrative approach transforms the book from a mere checklist into a compelling read about culture, history, and human connection through food.

Of course, a list of 1,000 items is bound to include some controversies. Some critics question the inclusion of ubiquitous items like the banana, arguing that it diminishes the exclusivity of the list. Others have noted a possible bias towards European and North American cuisines, though Sheraton defends her selections by pointing to the extensive research and personal travels that informed her choices. She emphasizes that the book is a personal, albeit expert, guide rather than a definitive, objective ranking. The goal, she states, is to inspire curiosity and appreciation, not to end debate.

Ultimately, 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die serves as a passport to gastronomic adventure. It challenges the reader to look beyond their culinary comfort zone, whether that means seeking out a rare ingredient, attempting a complex recipe at home, or simply ordering something unfamiliar at a local restaurant. For Sheraton, the book is a culmination of a lifetime’s passion for food, an invitation to savor the incredible diversity of flavors the world has to offer, one unforgettable bite at a time.

Questions 27-31

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE – if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE – if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN – if there is no information on this

27. Mimi Sheraton is currently working as a restaurant critic for the New York Times.

28. The book 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die was directly inspired by a popular travel guide.

29. Sheraton’s book includes recipes for every one of the 1,000 foods mentioned.

30. The book is organized according to the geographic origin of the foods.

31. Sheraton has been a food writer for six decades.

Questions 32 – 35

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet.

32. The main purpose of the first paragraph is to

A. criticize people’s boring eating habits.

B. provide specific examples of exotic foods.

C. explain the health benefits of a global diet.

D. introduce the book by highlighting its adventurous nature.

33. According to the passage, the book includes all of the following EXCEPT

A. historical background for certain dishes.

B. recommendations on where to find specific foods.

C. nutritional information for each food item.

D. a small number of full recipes.

34. How is the book’s structure described?

A. It is organized by country to make it easy for travelers.

B. It categorizes foods by their main ingredient.

C. It groups foods by the type of eating experience.

D. It is presented in a simple alphabetical list.

35. What is the author’s stated goal for the book?

A. To create an objective and definitive ranking of world foods.

B. To settle debates about the best cuisines.

C. To inspire curiosity and appreciation for diverse foods.

D. To promote European and North American restaurants.

Questions 36 – 40

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet.

Mimi Sheraton’s book has been described as a 36._____ for anyone who loves food. It is noted for its narrative approach, where each entry is like a mini 37._____ , explaining the cultural significance of a dish. While the book has faced some 38._____ , particularly over the inclusion of common items and a potential regional bias, Sheraton clarifies that the selections are based on her own 39._____ and expert opinion. The ultimate aim of the book is to encourage readers to expand their 40._____ and embark on a gastronomic adventure.

Đáp án:

|

27. FALSE |

34. C |

|

28. TRUE |

35. C |

|

29. FALSE |

36. gift |

|

30. FALSE |

37. stories |

|

31. TRUE |

38. controversies |

|

32. D |

39. research |

|

33. C |

40. comfort zone |

1.3. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 22.12.2025

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

The Impact of the Potato

Jeff Chapman relates the story of history the most important vegetable

A. The potato was first cultivated in South America between three and seven thousand years ago, though scientists believe they may have grown wild in the region as long as 13,000 years ago. The genetic patterns of potato distribution indicate that the potato probably originated in the mountainous west-central region of the continent.

B. Early Spanish chroniclers who misused the Indian word batata (sweet potato) as the name for the potato noted the importance of the tuber to the Incan Empire. The Incas had learned to preserve the potato for storage by dehydrating and mashing potatoes into a substance called Chuchu could be stored in a room for up to 10 years, providing excellent insurance against possible crop failures. As well as using the food as a staple crop, the Incas thought potatoes made childbirth easier and used it to treat injuries.

C. The Spanish conquistadors first encountered the potato when they arrived in Peru in 1532 in search of gold, and noted Inca miners eating chuchu. At the time the Spaniards failed to realize that the potato represented a far more important treasure than either silver or gold, but they did gradually begin to use potatoes as basic rations aboard their ships. After the arrival of the potato in Spain in 1570,a few Spanish farmers began to cultivate them on a small scale, mostly as food for livestock.

D. Throughout Europe, potatoes were regarded with suspicion, distaste and fear. Generally considered to be unfit for human consumption, they were used only as animal fodder and sustenance for the starving. In northern Europe, potatoes were primarily grown in botanical gardens as an exotic novelty. Even peasants refused to eat from a plant that produced ugly, misshapen tubers and that had come from a heathen civilization. Some felt that the potato plant’s resemblance to plants in the nightshade family hinted that it was the creation of witches or devils.

E. In meat-loving England, farmers and urban workers regarded potatoes with extreme distaste. In 1662, the Royal Society recommended the cultivation of the tuber to the English government and the nation, but this recommendation had little impact. Potatoes did not become a staple until, during the food shortages associated with the Revolutionary Wars, the English government began to officially encourage potato cultivation. In 1795, the Board of Agriculture issued a pamphlet entitled “Hints Respecting the Culture and Use of Potatoes”; this was followed shortly by pro-potato editorials and potato recipes in The Times. Gradually, the lower classes began to follow the lead of the upper classes.

F. A similar pattern emerged across the English Channel in the Netherlands, Belgium and France. While the potato slowly gained ground in eastern France (where it was often the only crop remaining after marauding soldiers plundered wheat fields and vineyards), it did not achieve widespread acceptance until the late 1700s. The peasants remained suspicious, in spite of a 1771 paper from the Facult de Paris testifying that the potato was not harmful but beneficial. The people began to overcome their distaste when the plant received the royal seal of approval: Louis XVI began to sport a potato flower in his buttonhole, and Marie-Antoinette wore the purple potato blossom in her hair.

G. Frederick the Great of Prussia saw the potato’s potential to help feed his nation and lower the price of bread, but faced the challenge of overcoming the people’s prejudice against the plant. When he issued a 1774 order for his subjects to grow potatoes as protection against famine, the town of Kolberg replied: “The things have neither smell nor taste, not even the dogs will eat them, so what use are they to us?” Trying a less direct approach to encourage his subjects to begin planting potatoes, Frederick used a bit of reverse psychology: he planted a royal field of potato plants and stationed a heavy guard to protect this field from thieves. Nearby peasants naturally assumed that anything worth guarding was worth stealing, and so snuck into the field and snatched the plants for their home gardens. Of course, this was entirely in line with Frederick’s wishes.

H. Historians debate whether the potato was primarily a cause or an effect of the huge population boom in industrial-era England and Wales. Prior to 1800,the English diet had consisted primarily of meat, supplemented by bread, butter and cheese. Few vegetables were consumed, most vegetables being regarded as nutritionally worthless and potentially harmful. This view began to change gradually in the late 1700s. The Industrial Revolution was drawing an ever increasing percentage of the populace into crowded cities, where only the richest could afford homes with ovens or coal storage rooms, and people were working 12-16 hour days which left them with little time or energy to prepare food. High yielding, easily prepared potato crops were the obvious solution to England’s food problems.

I. Whereas most of their neighbors regarded the potato with suspicion and had to be persuaded to use it by the upper classes, the Irish peasantry embraced the tuber more passionately than anyone since the Incas. The potato was well suited to the Irish the soil and climate, and its high yield suited the most important concern of most Irish farmers: to feed their families.

J. The most dramatic example of the potato’s potential to alter population patterns occurred in Ireland, where the potato had become a staple by 1800. The Irish population doubled to eight million between 1780 and 1841,this without any significant expansion of industry or reform of agricultural techniques beyond the widespread cultivation of the potato. Though Irish landholding practices were primitive in comparison with those of England, the potato’s high yields allowed even the poorest farmers to produce more healthy food than they needed with scarcely any investment or hard labor. Even children could easily plant, harvest and cook potatoes, which of course required no threshing, curing or grinding. The abundance provided by potatoes greatly decreased infant mortality and encouraged early marriage.

Questions 1 – 5 (TRUE/FALSE/NOT GIVEN)

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 1? Write:

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

1. The early Spanish called potato as the Incan name ‘Chuchu’

2. The purposes of Spanish coming to Peru were to find out potatoes

3. The Spanish believed that the potato has the same nutrients as other vegetables

4. Peasants at that time did not like to eat potatoes because they were ugly

5. The popularity of potatoes in the UK was due to food shortages during the war

Questions 6 – 13 (Sentence Completion)

Complete the sentences below with NO MORE THAN ONE WORD from the passage for each answer.

6. In France, people started to overcome their disgusting about potatoes because the King put a potato ________ in his button hole.

7. Frederick realized the potential of potato but he had to handle the ________ against potatoes from ordinary people.

8. The King of Prussia adopted some ________ psychology to make people accept potatoes.

9. Before 1800,the English people preferred eating ________ with bread, butter and cheese.

10. The obvious way to deal with England food problems were high yielding potato ________.

11. The Irish ________ and climate suited potatoes well.

12. Between 1780 and 1841, based on the ________ of the potatoes, the Irish population doubled to eight million.

13. The potato’s high yields help the poorest farmers to produce more healthy food almost without ________.

Đáp án:

|

1. FALSE |

8. reverse |

|

2. FALSE |

9. meat |

|

3. NOT GIVEN |

10. crops |

|

4. TRUE |

11. soil |

|

5. TRUE |

12. cultivation |

|

6. flower |

13. investment |

|

7. prejudice |

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-25, which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

Seaweeds of New Zealand

A. Seaweed is a particularly wholesome food, which absorbs and concentrates traces of a wide variety of minerals necessary to the body’s health. Many elements may occur in seaweed – aluminium, barium, calcium, chlorine, copper, iodine and iron, to name but a few – traces normally produced by erosion and carried to the seaweed beds by river and sea currents. Seaweeds are also rich in vitamins; indeed, Inuits obtain a high proportion of their bodily requirements of vitamin C from the seaweeds they eat. The health benefits of seaweed have long been recognised. For instance, there is a remarkably low incidence of goitre among the Japanese, and also among New Zealand’s indigenous Maori people, who have always eaten seaweeds, and this may well be attributed to the high iodine content of this food. Research into historical Maori eating customs shows that jellies were made using seaweeds, nuts, fuchsia and tutu berries, cape gooseberries, and many other fruits both native to New Zealand and sown there from seeds brought by settlers and explorers. As with any plant life, some seaweeds are more palatable than others, but in a survival situation, most seaweeds could be chewed to provide a certain sustenance.

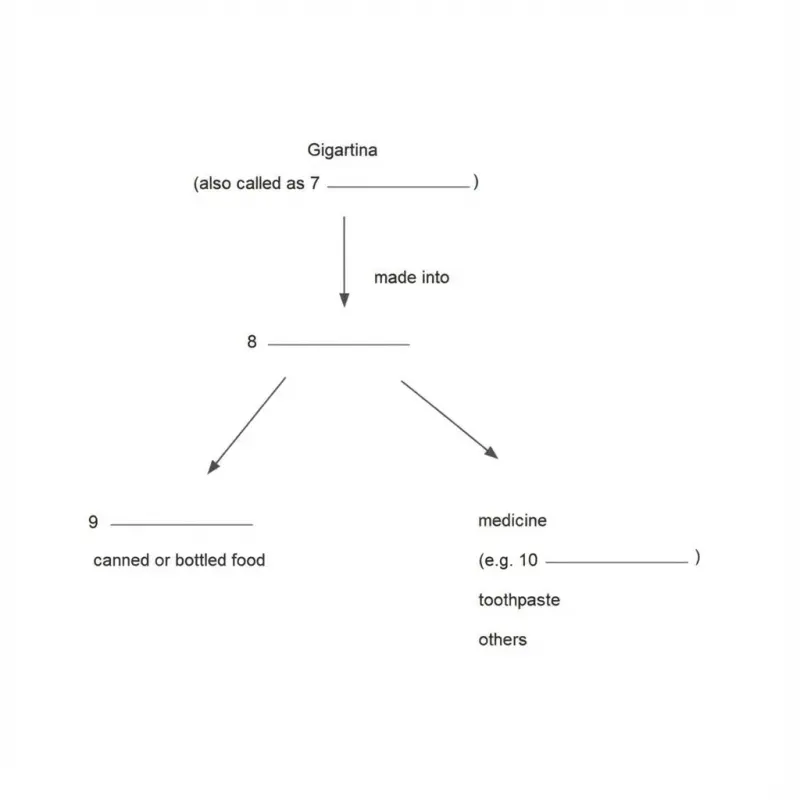

B. New Zealand lays claim to approximately 700 species of seaweed, some of which have no representation outside that country. Of several species grown worldwide, New Zealand also has a particularly large share. For example, it is estimated that New Zealand has some 30 species of Gigartina, a close relative of carrageen or Irish moss. These are often referred to as the New Zealand carrageens. The substance called agar which can be extracted from these species gives them great commercial application in the production of seameal, from which seameal custard (a food product) is made, and in the canning, paint and leather industries. Agar is also used in the manufacture of cough mixtures, cosmetics, confectionery and toothpastes. In fact, during World War II, New Zealand Gigartina were sent to Australia to be used in toothpaste.

C. New Zealand has many of the commercially profitable red seaweeds, several species of which are a source of agar (Pterocladia, Gelidium, Chondrus, Gigartina). Despite this, these seaweeds were not much utilised until several decades ago. Although distribution of the Gigartina is confined to certain areas according to species, it is only on the east coast of the North Island that its occurrence is rare. And even then, the east coast, and the area around Hokianga, have a considerable supply of the two species of Pterocladia from which agar is also made. New Zealand used to import the Northern Hemisphere Irish moss (Chondrus crispus) from England and ready-made agar from Japan.

D. Seaweeds are divided into three classes determined by colour – red, brown and green – and each tends to live in a specific position. However, except for the unmistakable sea lettuce (Ulva), few are totally one colour; and especially when dry, some species can change colour significantly – a brown one may turn quite black, or a red one appear black, brown, pink or purple. Identification is nevertheless facilitated by the fact that the factors which determine where a seaweed will grow are quite precise, and they tend therefore to occur in very well-defined zones. Although there are exceptions, the green seaweeds are mainly shallow-water algae; the browns belong to the medium depths; and the reds are plants of the deeper water, furthest from the shore. Those shallow-water species able to resist long periods of exposure to sun and air are usually found on the upper shore, while those less able to withstand such exposure occur nearer to, or below, the low-water mark. Radiation from the sun, the temperature level, and the length of time immersed also play a part in the zoning of seaweeds. Flat rock surfaces near midlevel tides are the most usual habitat of sea-bombs, Venus’ necklace, and most brown seaweeds. This is also the home of the purple laver or Maori karengo, which looks rather like a reddish-purple lettuce. Deep-water rocks on open coasts, exposed only at very low tide, are usually the site of bull-kelp, strapweeds and similar tough specimens. Kelp, or bladder kelp, has stems that rise to the surface from massive bases or ‘holdfasts’, the leafy branches and long ribbons of leaves surging with the swells beyond the line of shallow coastal breakers or covering vast areas of calmer coastal water.

E. Propagation of seaweeds occurs by seed-like spores, or by fertilisation of egg cells. None have roots in the usual sense; few have leaves; and none have flowers, fruits or seeds. The plants absorb their nourishment through their leafy fronds when they are surrounded by water; the holdfast of seaweeds is purely an attaching organ, not an absorbing one.

F. Some of the large seaweeds stay on the surface of the water by means of air-filled floats; others, such as bull-kelp, have large cells filled with air. Some which spend a good part of their time exposed to the air, often reduce dehydration either by having swollen stems that contain water, or they may (like Venus’ necklace) have swollen nodules, or they may have a distinctive shape like a sea-bomb. Others, like the sea cactus, are filled with a slimy fluid or have a coating of mucilage on the surface. In some of the larger kelps, this coating is not only to keep the plant moist, but also to protect it from the violent action of waves.

(Nguồn Internet)

Questions 14-19

Reading Passage 1 has six paragraphs, A-F.

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below. Write the correct number, i-ix, in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

Paragraph A

Paragraph B

Paragraph C

Paragraph D

Paragraph E

Paragraph F

List of Headings

i. The appearance and location of different seaweeds

ii. The nutritional value of seaweeds

iii. How seaweeds reproduce and grow

iv. How to make agar from seaweeds

v. The under-use of native seaweeds

vi. Seaweed species at risk of extinction

vii. Recipes for how to cook seaweeds

viii. The range of seaweed products

ix. Why seaweeds don’t sink or dry out

Questions 20-23

Using the image provided, complete the flowchart below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Questions 23-26

Classify the following characteristics as belonging to:

A. brown seaweed

B. green seaweed

C. red seaweed

23. can survive the heat and dryness at the high-water mark

24. grow far out in the open sea

25. share their site with karengo seaweed

Đáp án:

|

14. v |

21. agar |

|

15. ii |

22. seameal |

|

16. viii |

23. cough mixture |

|

17. i |

24. B |

|

18. iii |

25. C |

|

19. ix |

26. A |

|

20. New Zealand carrageens |

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40, which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

The Peopling of Patagonia

Anthropologists continue to investigate human migration to Patagonia at the southern tip of South America.

The human settlement of the southern extremity of the Americas has always fascinated pre-historians. Viewed from a global perspective, this was the last major continental land mass to be reached by human beings. The earliest occupation of Patagonia carries obvious implications for understanding when the North and South American continents were peopled, because it gives a baseline that all calculations regarding the rate of dispersion of humans throughout both continents must take into account.

For many years the human settlement of North and South America has been conceived of as beginning in the far north and travelling progressively southwards to Patagonia. However, fundamental disagreements developed concerning the length of time involved. Some scholars accepted a human presence in the Americas as early as 20,000 years ago, while others proposed that it could date no earlier than 8,000 years ago, and the debate is still with us today.

The idea of a relatively “late” settlement of the Americas (around 8,000 years ago) implies that a rapid process of migration took place. Herein lies a second debate which revolves around the question of how migration is to be understood. The late model demands a hypothetical migration conceived of as a single, continually advancing wave of settlement. This has always been difficult to take seriously and many scholars now support the idea of an early model that sees the migration as a less ordered migration, and this is surely the most realistic scenario as migrants slowly adapted to the diverse natural habitats they would have met while travelling through the continent.

Those who argue for an earlier settlement, however, must contend with the lack of unequivocal evidence for archaeological sites older than around 14,000 years. Nevertheless, evidence for human occupation of the centre of South America is now securely dated to around 12,500 years ago at the Monte Verde site, which casts doubt on the late model. The lack of archaeological evidence further south for this time period may be explained by the obstacle to humans on foot posed by the huge glacial streams that were present at that time.

We can speculate then that the retreat of the Patagonian glaciers around 14,000 years ago allowed the initial human intrusion into a pristine environment, which was similar to that of early post-glacial Europe. Human settlement of the vast horizontal expanse of treeless high country must have been tenuous at best, and the evidence for this occupation remains relatively scant, most of it coming from rock shelters in Argentina and Chile. There is, however, reliable evidence from these sites to confirm the presence of humans by around 11,000 years ago in different habitats, and some hints of an even older occupation. However, some other sites where evidence for even earlier human occupation was initially posited, have recently come under fresh scrutiny. This is because anthropologists have come to recognise that bones or other evidence may be deposited in caves by natural agency, in other words by other forces such as floods or predators, and not necessarily by humans.

We shall turn now to a more detailed discussion of the archaeological evidence found in various parts of Patagonia. At the site located beside Chinchihuapi Creek, excavations have produced convincing evidence of human occupation, including hut foundations and wooden artefacts. They were buried in layers of peat, which has the property of preserving wood remarkably well, and as a result radiocarbon dating tests have shown these artefacts to date from around 12,500 years ago. One of the most famous Patagonian sites is a cave known as Los Toldos. However, the evidence from this site has recently been called into question, because dispersed flecks of carbon used in the test process were taken unsystematically from many different places in the site. As a result, the association of this material with the artefacts is not at all clear. About 150 kilometres south is the site called El Ceibo, where a similar collection of artefacts to that found at Los Toldos has been discovered from the lowest levels of the dig, but as yet no radiocarbon dates are available and this sort of analysis of the existing evidence is required before the site’s value can be confirmed.

The Arroyo Feo site is located very close to the high plateau. The artefacts from the earliest occupations were found at the same depth and have the same origins as those from Los Toldos, and have been securely dated to around 9,000 years ago. Another site that is mentioned in the debate is at Las Buitreras, where a number of stone flakes associated with bone remains of various animals have been discovered. However, anthropologists now believe that presumed cut marks on the bones are somewhat dubious, and despite detailed testing there is no way of securely relating any of these remains with human occupation. Finally some 50 kilometers to the south is the site at Cueva Fell, which was the first Patagonian site to be systematically studied by modern archaeological methods. However, it is now recognised that the utility of this site must be restricted to its direct vicinity, given changes to the nearby area caused by flooding, and findings cannot be freely extrapolated further afield.

In conclusion, based on the evidence from a number of reliable sites, it seems probable that human populations reached Patagonia around 11,000 years ago.

Questions 27-31

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet.

27. In the first paragraph, what is the writer’s main point about migration to Patagonia?

A. It started earlier than previously thought.

B. Historians have overlooked its importance.

C. It impacts on research into the wider region.

D. Researchers have calculated its effects on the environment.

28. In the second paragraph, what is the writer’s purpose?

A. to challenge previous research

B. to propose new areas to investigate

C. to summarise a scholarly debate

D. to suggest reasons for human migration

29. The writer refers to the “late” model in order to

A. compare it with another theory of migration.

B. evaluate the success of American migration.

C. criticise the speed of research into migration.

D. compare migration in different parts of the world.

30. What is the writer’s main point about the “early model”?

A. Scholars support the idea of fast migrations.

B. It is too random to be a convincing theory.

C. South America was more habitable at an earlier time.

D. It is more consistent with the physical conditions of the land.

31. What does the writer suggest about the Monte Verde site?

A. It is much younger than researchers once estimated.

B. It provides supporting evidence for relatively early settlement.

C. Archaeologists believe the site is of questionable value.

D. Streams exposed the site, making new research possible.

Questions 32 – 35

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

32. The conditions encountered by the first migrants to Patagonia were unique.

33. In the high country the first migrants hunted wild animals for food.

34. Archaeologists have failed to draw conclusions from the evidence found at rock shelters in Argentina and Chile.

35. Archaeological evidence can be moved from place to place in a variety of ways.

Questions 36 – 40

Complete the summary using the list of words and phrases, A-J, below.

Write the correct letter, A-J, in boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet.

The archaeological evidence from Patagonia

Building remains and other evidence have been found in 36………………….… at the Chinchihuapi Creek site, and because of this it has been possible to date them to around 12,500 years ago. However, the 37………………………………...of the samples taken from Los Toldos means that this site is of doubtful value. El Ceibo is a more promising dig, where the examination of artefacts would be beneficial in order to confirm the usefulness of discoveries there. The remains found at the Arroyo Feo site show 38…………………………….………and date from around 9,000 years ago. Unfortunately no 39…can be made between the samples taken from Las Buitreras and human presence. The findings of the work carried out at Cueva Fell cannot provide useful information beyond the 40. In conclusion, though the evidence is mixed, it is believed that human population of Patagonia began about 11,000 years ago.

A fixed date

B random collection

C similar properties

D good condition

E scientific evaluation

F huge quantities

G new samples

H reliable connection

I skilled preservation

J immediate surroundings

Đáp án:

|

27. C |

34. NO |

|

28. C |

35. YES |

|

29. A |

36. D |

|

30. D |

37. B |

|

31. B |

38. C |

|

32. NOT GIVEN |

39. H |

|

33. NOT GIVEN |

40. J |

1.4. Đề thi IELTS Reading ngày 24.11.2025

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

Dolls Through the Ages

What is today a simple children’s toy has a surprisingly rich history. Dolls have been a part of humankind for thousands of years. Often depicting religious figures, or used as playthings, early dolls were probably made from primitive materials such as clay, fur, or wood.

Dolls constructed of flat pieces of wood, painted with various designs, and with hair made of clay, have often been found in Egyptian graves dating back to 2000 BC. Egyptian tombs of wealthy families have included pottery dolls. Dolls being placed in these graves leads some to believe that they were cherished possessions.